Occupy their Expert Heuristics

How do we know which public expert to trust? It's the one that looks and sounds like the one we would trust, of course. The one that occupies our public expert heuristics.

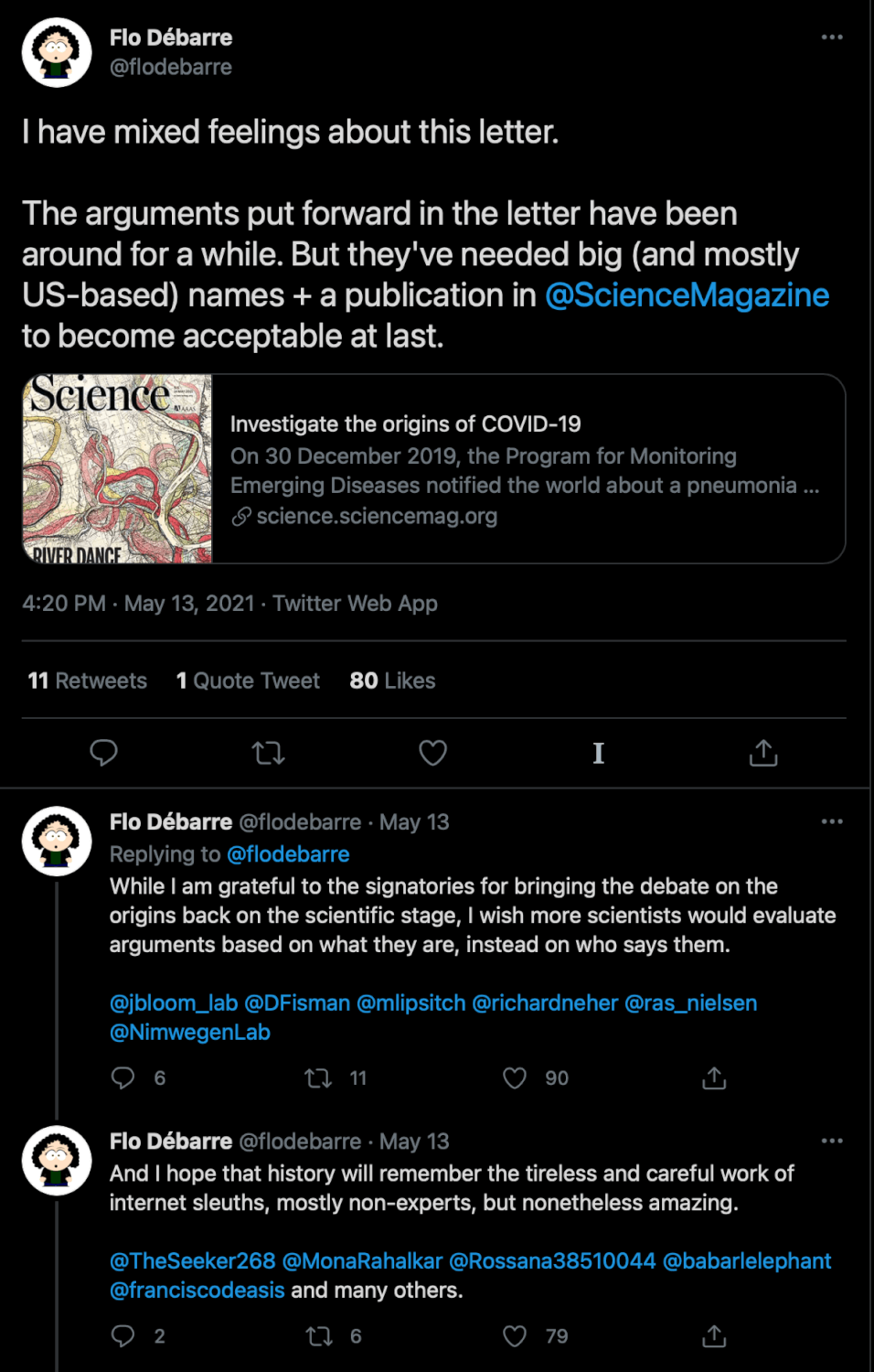

Flo Débarre, an evolutionary ecologist at the French National Center for Scientific Research, tweeted the following last month in the wake of a letter in Science signed by 18 scientists calling for an investigation into the origins of COVID-19:

Débarre’s is a common scientist position — what a shame scientists let such non-scientific factors such as name recognition and hero worship obscure scientific merit. Imagine a communications team waiting around for a more powerful comms group to recognize its efforts, all the while griping that it had to rely on people with more clout. It’s petulant and unworldly. It has no sense of heuristics in it. Scientists have simply got to stop waiting around for a society (and a science) we will never have, and figure out how to work better with the one that’s here.

But one the signatories of the Science letter that Débarre tagged, the Harvard infectious disease epidemiologist Marc Lipsitch, took Débarre’s thread seriously and replied with this long thread on how he figures out whom and what to trust on topics he isn’t an expert on. Lipsitch’s thread demonstrates one essential element of trust — that it is a series of heuristics — while forgetting another essential element: that trust means a relationship, borne of heuristics occupied over time.

Lipsitch starts with a rule of thumb: Trust no one intrinsically. Instead, trust good arguments. Débarre would approve — but Lipsitch realizes this rule creates an immediate problem. Almost none of us can properly evaluate any argument directly — from diabetes epidemiology to the US withdrawal from Afghanistan — as experts. So we must use public expert heuristics to decide which people are really experts and which of their arguments to trust. Lipsitch lists his heuristics, including:

Does he know the person?

Do they have a degree in a relevant field?

Where do they work?

Are their positions predictable (not always a plus) or surprising (a plus)?

Do they ever admit ignorance or correct their errors publicly?

Do they refute contrary evidence in a non-dismissive fashion?

Do they have a basic understanding of fact vs. speculation vs. opinion?

No combination of heuristics are ever ideal, Lipsitch concludes — but since “having a truly informed opinion on most matters is beyond our time constraints,” we must fall back on using them to recognize trusted sources. Authorities. Public experts.

Authority takes time. Trust is a relationship. (And remember: Trust isn't just about expertise.) It’s easy to make fun of some of Lipsitch’s criteria, but taken together, his still say: I have watched you, listened to you and I think I can trust you. You occupy the public expert heuristics that matter to me.

And while science (not to mention Science) can be grossly unfair, you also don’t build a community by wishing for a level playing field or that the public be better informed. You build it by delivering valuable insights and occupying the public expert heuristics your communities will respond to.