Power, Media, Science & Public Experts

How odd: Researchers who are otherwise exquisitely aware of the inequities power causes in the world — and in science — are often blind to those inequities when it comes to who gets to talk about research and who makes that happens.

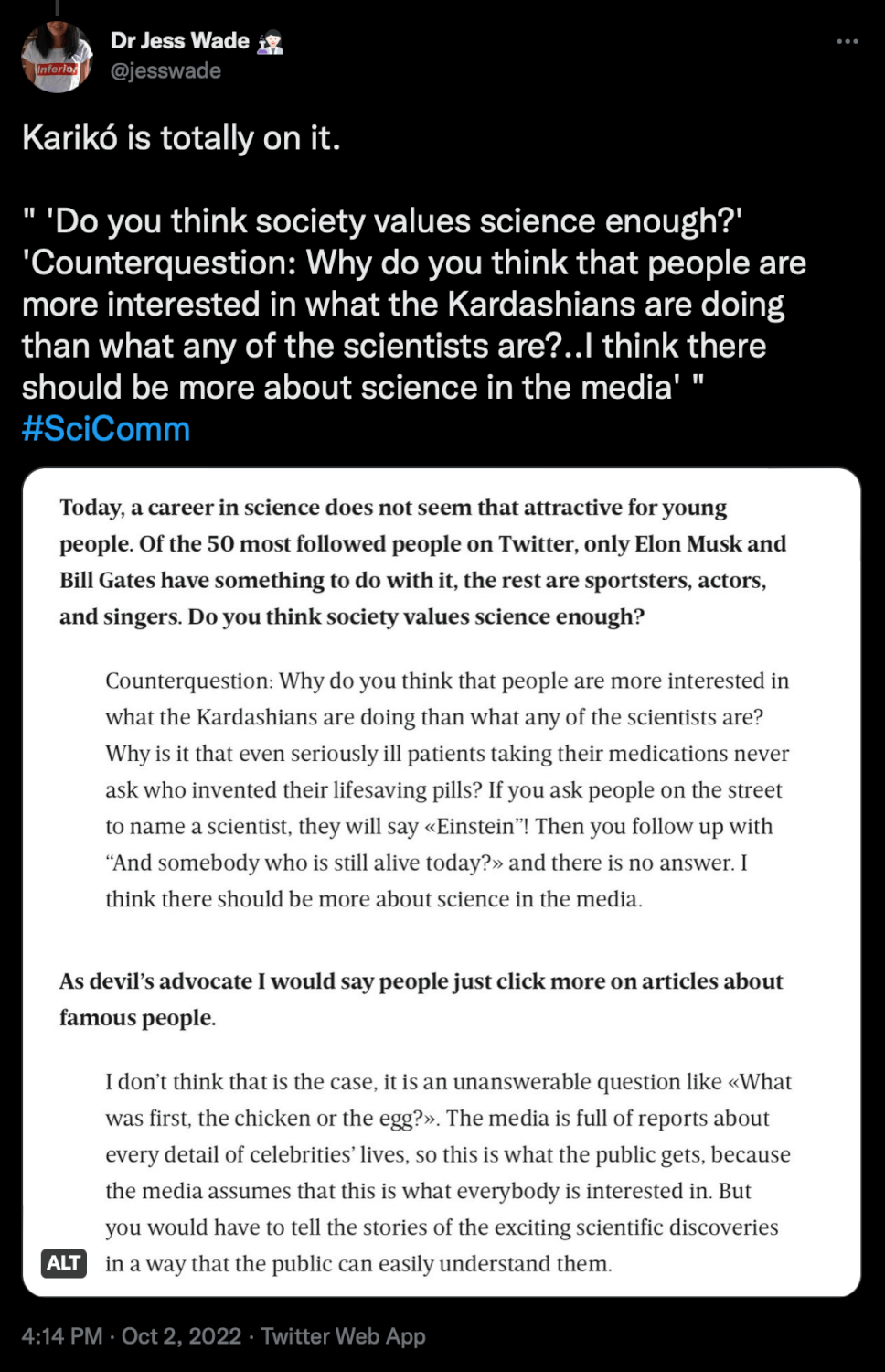

In a fascinating interview with the magazine Aargauer Zeitung, Hungarian-American scientist Katalin Karikó (now legendary for her contributions to the development of the mRNA vaccine) talks about discrimination against women in science (and the problem that she thinks is at least as dangerous for the industry); the thoroughgoing elitism in science that makes proposals in unfamiliar areas extremely difficult to get funding for; and why doing work in a marginalized field might be liberating for a scientist (or at least was for her).

Also, Karikó says this:

This is not the way all researchers think about the media. But it is still the way too many researchers think about the media — as in, not thinking at all.

As an indictment of the media economy, Karikó’s complaints are silly on several levels:

The media have a hypersensitive handle on what their audiences do and don’t respond to. Spectacular failures such as CNN+ aside, they no more make untested assumptions about what the public wants than do scientists skip experiments because they assume their hypotheses are correct.

The media have no obligation to tell “exciting scientific discoveries in a way that the public can easily understand them,” particularly because most scientific discoveries are never going to be exciting (to non-scientists) and because most of science is not about discoveries, but about the grinding advance of the literature despite innumerable blind allies and false starts.

Finally, people have not been brainwashed by celebrity culture into incuriosity about science. Even seriously ill patients who do ask who invented their lifesaving pills would find out it wasn’t a “who” so much as a faceless corporate science team.

What’s strange to me is that Karikó — who spent so much of her early scientific career shut out of science’s prestige and money centers, often finding herself between labs and funding — thinks there will be anything meritocratic about a research marketing model that depends on a) the media for production and distribution, and b) elite university/corporate science hype machines for raw material. You know, like the one we have now.

The lesson Karikó takes away from media neglect of science — that the media should be mandated somehow to tell science stories — is the opposite of the one she took away from her own early career struggles:

You will find that after specializing in something, there will always be a colleague who works less, who is promoted before you or who makes more money than you. That makes a lot of people feel disappointed, especially now that society is more egocentric. But I tell you that if you pay attention to that, you pay less attention to things that you can change. Everything must end with the question: What can I personally do better? Because your circumstances often cannot be changed.

Agreed! And this also holds for being a public expert. Being a public expert is an exploration in how you can take back control of your own expertise and your relationship with people who might benefit from it.

The exploration consists of asking Karikó’s question and then continuing to ask it — about the channels you own, the messages you convey, the audiences you target and build, the dialogues you foster with those audiences and (yes) the media you cultivate.

Or you can wait for your insights to be discovered — a solution that, when it came to her science, Karikó knew was no solution at all.