One Bad Habit Twitter Has Left Researchers

Not flagging "expert" vs. "personal" online leads to stupid fights and loss of trust.

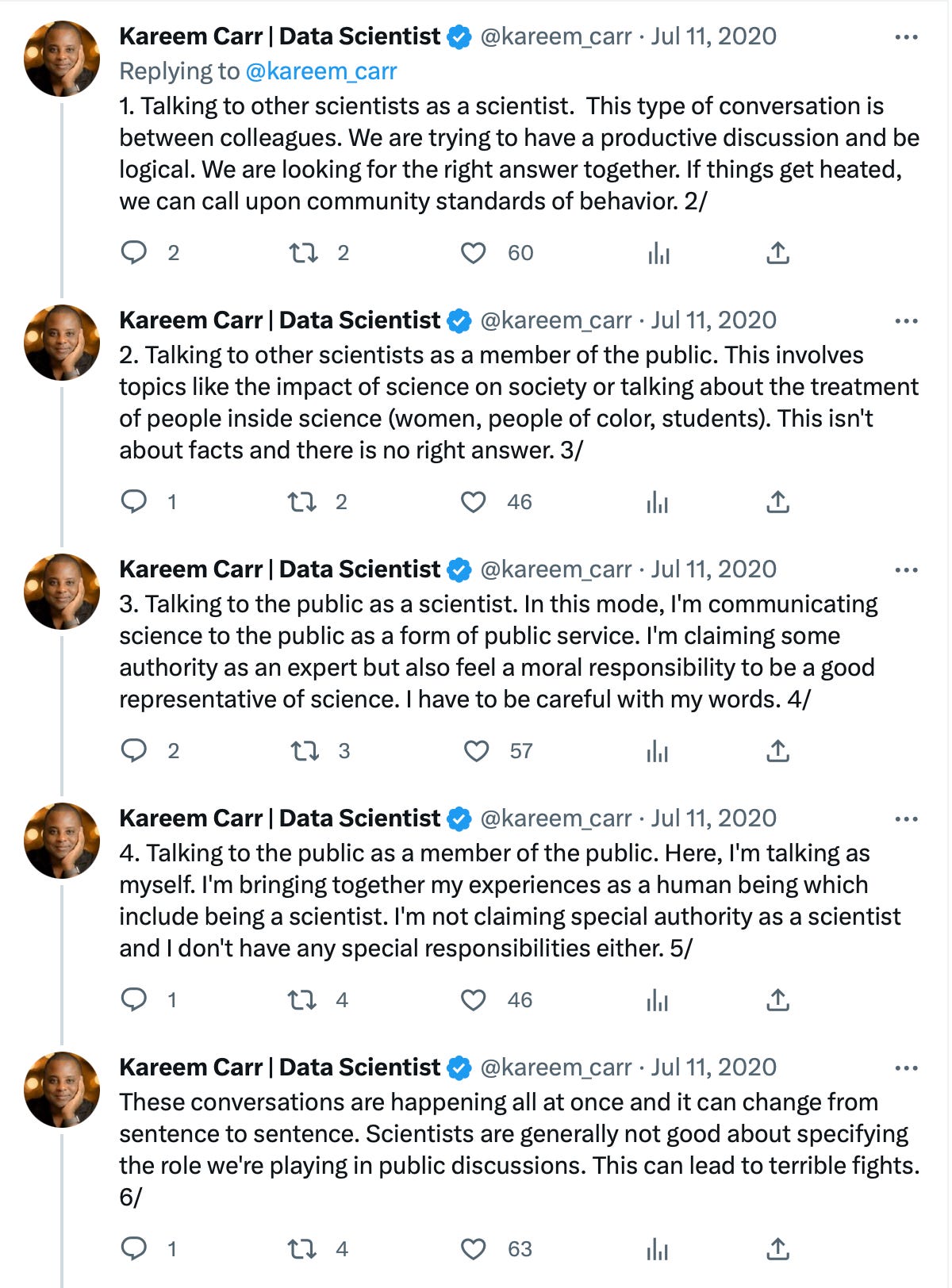

Twitter might be dying — but Twitter bad habits are going to be hard to let go of for a lot of researchers. One of the worst of these habits: Assuming the perks of expertise — its claims to authority and rationality — no matter if you’re speaking as a peer, citizen or expert. The data scientist Kareem Carr wrote a thread during the first summer of the pandemic — about the four possible ways for scientists to have a conversation on Twitter — that I still think a lot about because it explains why so many researchers still walk into propellers on Twitter:

I’d argue that the problem isn’t just that the rest of Twitter is confused about who researchers are — so are researchers on Twitter, because it rewards you for being personal most of the time.

I’m not arguing for going back to the good old days when we pretended to keep personal and professional in separate buckets. But assuming you can float between expert and personal and political mode and claim the mantle of authority in all of those modes is just bad communications on every platform, and Twitter isn’t an exception. Carr nails the problem in that last tweet: “These conversations are happening all at once and it can change from sentence to sentence. Scientists are generally not good about specifying the role we’re playing in public discussions. This can lead to terrible fights.” Conventional science communications tells us to be more personal as the way to engender trust. But the evidence of Twitter and elsewhere shows that it can just as easily lead to loss of trust in the expert if the expert doesn’t handle the personal mode clearly.

The Nature Endorsement of Biden

The Nature Biden endorsement illustrates how the unacknowledged tension between expert and personal/political can extend beyond Twitter. In 2020, the journal/magazine Nature in 2020 endorsed Joe Biden for US president, one of the few times in its 154-year history that publication has taken sides in a political race. The endorsement listed all the particulars — slashed funding, closed science offices, gag orders — about Trump as a threat to science. Last week, Nature Human Behavior (a journal in the Nature family) published research that asked whether that endorsement changed any minds. Short answer: No, not about the candidates, but yes about Nature as a trustworthy publication (in a big negative way for Republicans and a much smaller positive way for Democrats). So the intervention was a clear net loss for Nature and probably for science, too.

But instead of reconsidering their endorsement policy, Nature’s editors doubled down with a second editorial declaring that, regardless of the Nature Human Behavior study’s findings, publishing that first editorial was the right thing to do — and that Nature will continue to endorse candidates when necessary, because (their words) “when candidates threaten a retreat from reason, science must speak out.” (As justification for its continued position, the second editorial argues that “influential political voices are eschewing rigorous evidence” — which, of course, the journal itself is also doing in this case.) Holden Thorp, the editor-in-chief of Science magazine, also came to the defense of Nature defending science (if not Science or Science)

Later, Thorp added that “following the admonition to stick to science is conceding the idea that scientists can be sidelined in policy decisions. ‘Stick to science’ infantilizes scientists and tells us to sit at the kids table and let the adults decide.” (Thorp has since walked back this bravado, at least for Science’s family of journals.)

Josh Barro and Matt Yglesias have written interesting takedowns of why this is all ridiculous, which amount to the following: Experts and expert institutions need to be very careful with political hobbying and performative moralizing, because a single instance of sounding biased can forfeit huge audiences’ trust in your research, and part of your job as a public expert is to not forfeit trust.

This all might seem obvious if you’re outside Science Twitter — that repudiating actual science by scientists in the name of defending science is bizarre, hypocritical and sadly exemplary of today’s thoroughgoing polarization. The question is: Why isn’t it obvious to Thorp and the editors of Nature?

Because if you’ve been part of Science Twitter for the last decade or so, pro-science, anti-anti-science performance and affirmation has been a big part of your bubble. The platform has convinced you that performance is crucially important — at least as important as, oh, a pre-registered, peer-reviewed study that shows otherwise. And — just as corrosive — your authority as a scientist extends to that performance, even if the data contradicts you.

“Just tweet more mindfully” is the kind of response extremely online people make to each (and always fail to follow). It fails to acknowledge how much the structure of Twitter has shifted what experts think is normal for their own communications vs. what most of the public expects from them. As your Twitter bubble implodes and you disengage from the platform, you might find the rest of the world’s standards and expectations weird and disorienting. Chances are that’s how they found yours on Twitter.