Beyond the Content Water Bra

It’s a researcher’s nightmare: You give a talk about a problem, and it’s a great talk — except for one thing: Your audience of important decision-makers, who started texting and scrolling through their email about five minutes into your talk, doesn’t just want to hear so much about problems. They want to get to the punchline, and you don’t have one; you just threw some generalized solutions for the problem in at the end of your talk like a twist on a martini. Now you’re trying to expand on these solutions in Q&A, but really, you’ve got nothing and you’re fooling no one. As you walk back to your seat, flushed with shame, you know you’ll never again be asked to share your insights with anyone important. (Relax: It’s just a bad dream. Right?)

Decision-makers and their craving for the solutions punchline — every researcher who’s also a public expert knows the cliche. It’s why we’ve been trying to convincingly cram problems and solutions into 800 words for op-ed editors since Jesus left Chicago. What a relief, then, to read Cassandra Naji of the content strategy group Animalz, tell us that successful expert content should enable its target audience to do only one thing — do something or think something. Tactics or strategy, solution or problem — not both. Trying to combine the two in a single piece of content, Naji argues, is akin to recreating the Evian Water Bra, a calamitous Frankenstein of a product.

I know: You want to hear more about this Water Bra. First, how does Naji define “tactical” vs. “strategic” content?

Tactical content appeals to people who need a specific solution now — how to write a killer email subject line, how to housebreak their dog, how to fill out a visa form. Tactical content can rank high in search for precisely that solution, but it often doesn’t do well in social for the same reason. (How many of your followers are housebreaking their dogs right now?)

Strategic content, on the other hand, is meant to give executives and other decision makers big new ideas and frames that a) challenge their usual ways of thinking and b) suggest (but not necessarily map out) solutions. Unlike tactical content, strategy content performs poorly on search (because no one knows about a big new idea enough to search for it). But strategic content can potentially perform very well on social, because it’s authoritative and probably polarizing. For the same reasons, it can also help build your brand with a very targeted audience of potential collaborators (if you’re a researcher) and buyers (if you’re a researcher selling products).

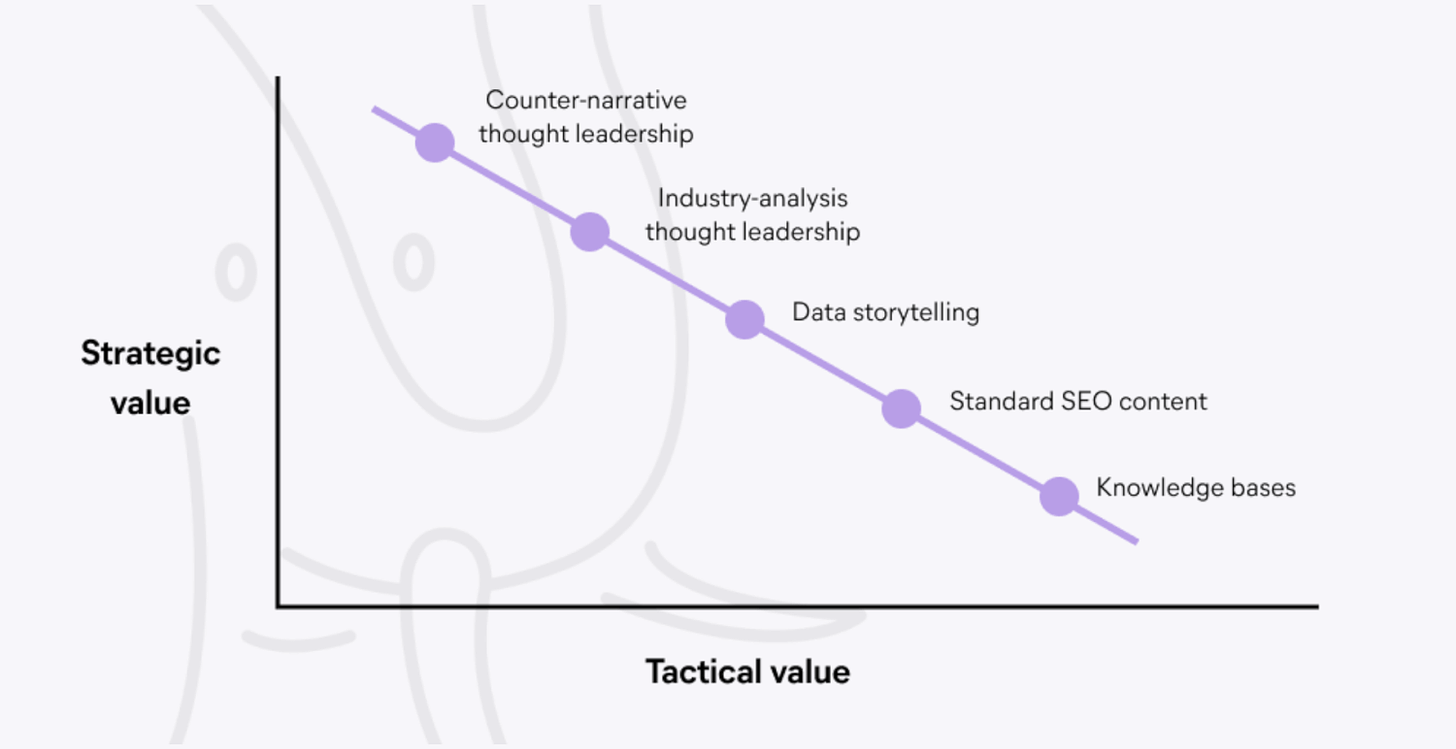

Now, researchers (even those who are public experts) don’t normally think this deeply about audiences and their needs. Naji says that’s a mistake: Tactical and strategic information are for very different audiences who do very different things — so they mix like chalk and cheese. “Generally, the more strategic value a piece of content adds, the less likely it is to add tactical value, and vice versa,” Naji writes, calling this inverse relationship “the content value curve.” Here’s a graphic from Naji’s Animalz blog post depicting the content value curve and where typical genres of content might fall along it:

If you try to mix strategic and tactical content in the same piece of content, Naji says, that’s like the bra Evian brought to market about 15 years ago that also contained a pouch that could hold a bottle of Evian water, presumably so one could carry one’s hydration discretely while exercising. Not surprisingly, the Water Bra was an immediate failure, “discontinued right after launch,” writes Naji, “brought low by its putative value prop — its multi-functionality as both garment and drinks-holder.” Now, you can and should mix tactical and strategic content in the same organizational content strategy, Naji adds…just not in the same piece of content.

I’m drawn to the content value curve: It visualizes nicely the tradeoffs researchers often have to make communicating with nonspecialists. Any public expert or expertise organization should always have a very good idea of what content format — from counter-narrative thought leadership to knowledge base — might foreground what level of value. The curve is a great start at visualizing those goals and tradeoffs.

But while I’m also drawn to the idea of doing one thing well in content, experience tells me the content of public experts still needs to address both problems and solutions, for two reasons.

First, there’s far less separation in our audiences between “people who think about strategy” and “people who think about implementation.” Decision-makers often are people who think about strategy together with its implementation all the time.Segmenting tactics from strategy is like segmenting shipping logistics from Christmas. Instead, persuading on strategy requires persuading on tactics as manifestations of that strategy, like this PNAS opinion piece on how to govern the open ocean beyond national jurisdiction in an equitable fashion.

Second, the content value curve seems to assume that you have audiences’ attention over an extended arc and that you can target any given audience (geared toward implementation or strategy) at will — that you have a segmented distribution strategy to which you need to match your content strategy. Most researchers and research-based organizations don’t have that targeting capacity. And most get at best serendipitous opportunities to address any given audience beyond their small core one. Your situation is less “I’ll talk about strategy with them today, then about tactics next week” and more like the nightmare I opened this essay with — one shot to impress them.

I agree that the content water bra sounds horrible. But expert content that frames up the real problem and also the solution to that problem sounds…reasonable, even expected of public experts. That’s because it is.