All the Right Science Communication Things

Many public health experts have been rending their clothes for the last two years over the abysmal messaging from the White House on all matters COVID.

Now the White House has a master messager: Ashish Jha, the White House coronavirus czar. Witness Sha’s new Q&A in the New Yorker, in which he sounds like a scicomm text book. Some highlights:

Communicating your research is the cake, not the icing.

Research best combats misinformation when researchers go public with what they know as soon as they know it, instead of waiting to lock everything down scientifically and allowing the misinformationists to define the conversation.

Research that could make a difference in people’s lives won’t make that difference unless you work to translate it into policy.

Science communication isn’t just a long game, it’s an extended ground game. Don’t give up at an initial negative response, and never write anyone off.

The pandemic phase we’re in right now is still unacceptable — still too many deaths, still too much disruption. It might continue for another year, but we will not be living like this three to five years from now.

It’s that last one that snapped me out of my science-communications-best-practices-drinking-bird-nod. Because: What’s the path from where we are now to that better, pandemic-free world three to five years from now? Is it just doing all the right science communication things?

And doesn’t that list start to look platitudinous once you consider it from the uncertainty of the end result?

What is Jha doing? Walking a perhaps non-existent tightrope between messaging two different audiences, writes STAT’s Lev Facher: the public, many of whom feel the pandemic is over and have a lot of other bad news to wade through; and Congress, whom the administration wants to wrangle additional vaccine and other anti-COVID funding from to combat a potentially catastrophic winter wave of infections.

Or reinfections. Eric Topol just wrote about a new large study of the risks of COVID reinfections vis-a-vis health outcomes — the findings won’t soothe you. Compared with people who have had only one infection, those with two or more infections have double the risk of all-cause mortality, double the risk of cardiovascular and lung adverse outcomes, and three times the risk of hospitalization. You do not want to get COVID multiple times — and the new variants of Omicron are showing much more immune escape and elusiveness against the original vaccines than Omicron-BA.1.

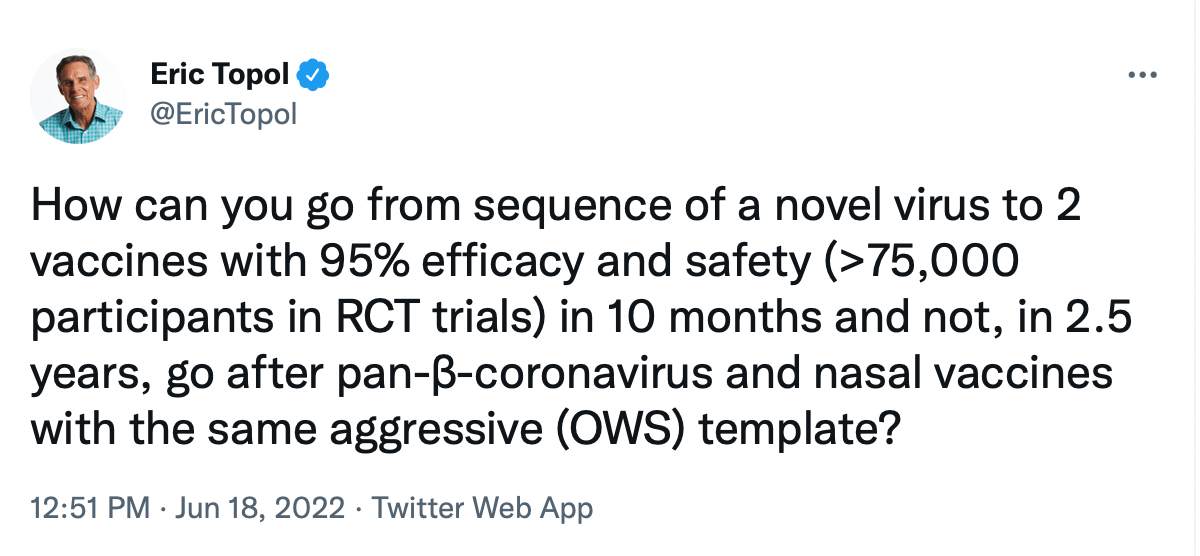

Topol’s list of to-dos is equally lacking in comfort: It’s mostly reinstating the old playbook — masking (and properly), distancing, proper indoor ventilation and filtration, and getting a (fourth) booster. But he adds one note of what he calls his “#1 frustration”:

“There is simply no excuse for why these vaccines are not being hyper-aggressively pursued,” Topol writes. “If ever there was a callout for don’t just stand there, do something, this is it.”

That's Jha's department, as well as that of Congress. Of course, Jha can’t say something that blunt and necessary — at least not publicly. As Facher notes, he has made clear his preference for publicly professing optimism, as has the Biden administration (including the suddenly silent CDC).

Interesting, though, how optimism can neatly include — indeed, rely on — saying all the right science communications things. I would have thought them that practical, but not that vaguely comforting.